Give not thyself up, then, to fire, lest it invert thee, deaden thee; as for the time it did me. There is a wisdom that is woe; but there is a woe that is madness. And there is a Catskill eagle in some souls that can alike dive down into the blackest gorges, and soar out of them again and become invisible in the sunny spaces. And even if he for ever flies within the gorge, that gorge is in the mountains; so that even in his lowest swoop the mountain eagle is still higher than other birds upon the plain, even though they soar.

Herman Melville, Moby Dick

Many whom quote this passage omit the first line. While this broadens the quote, it trims away Melville’s ambivalence. Trim ambivalence at your peril. Ishmael has spent the night staring into the flames and lost all sense for a time. He muses this as he at last comes out of it. That we, too, wish to forget the suffering and sacrifice that accompanies his eagle–and perhaps the hint of over-earnest rationalization–when sharing this passage should tell us much.

Before this quote, Ishmael has just broken free from his mad spell and warns us:

Look not too long in the face of the fire, O man! Never dream with thy hand on the helm! Turn not thy back to the compass; accept the first hint of the hitching tiller; believe not the artificial fire, when its redness makes all things look ghastly. To-morrow, in the natural sun, the skies will be bright; those who glared like devils in the forking flames, the morn will show in far other, at least gentler, relief; the glorious, golden, glad sun, the only true lamp- all others but liars!

Ibid.

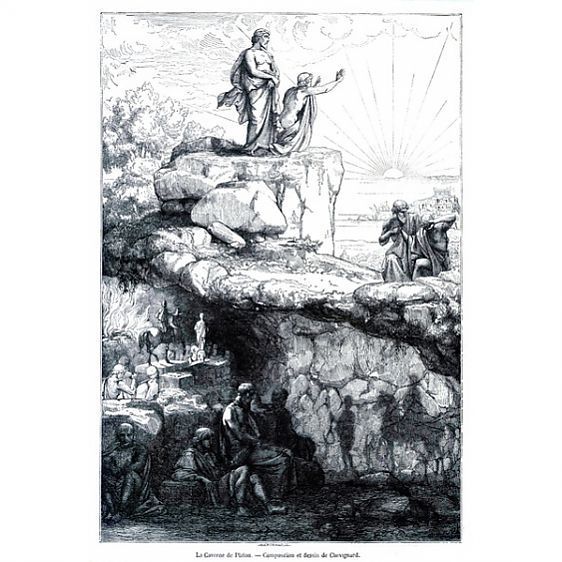

To soar out from the blackest gorges. Or perhaps from a particular flame lit cave?

The entire chapter–The Try-Works–is worth a read. And, well, I’d hardly stop there.