We are witnessing one of those great convergences, where everything suddenly seems to change all at once but is really the end of long-existing and ignored stresses reaching their logical conclusion. Like a house collapsing from years of neglect, each event seems abrupt and random and terrible when it is a miracle it all didn’t collapse years before.

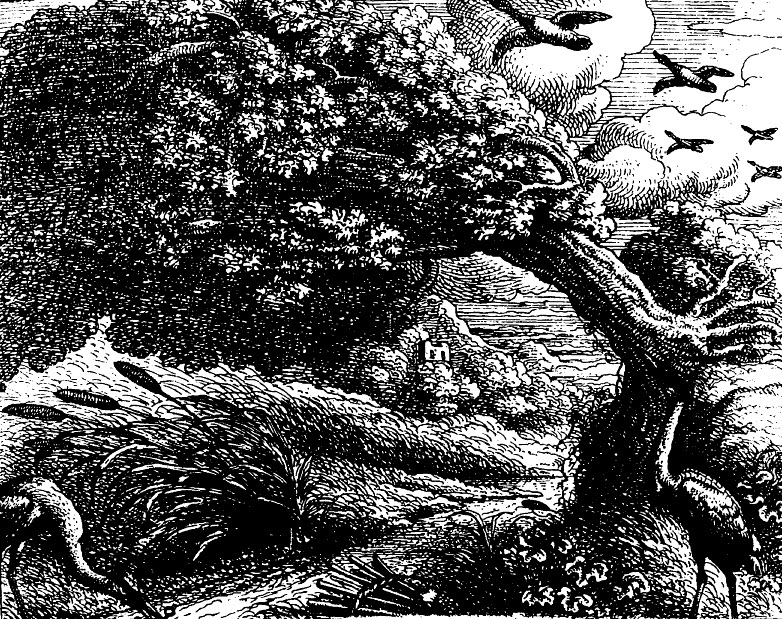

I’ve been picking my way through Taleb’s AntiFragile. As the author meanders his way–often charmingly–around the same basic points a few dozen times, one that sticks with me is the idea of hidden fragility. Not all fragile things simply shatter like porcelain upon the first hard impact. Some behave more like that oak in the yard you always thought a little too close to the house. It’s stood up to a thousand storms and then, suddenly after a minor gust, half the tree is resting on your roof. Or, deeply shaking you, the entire thing uproots while everything around it seems untouched.

An oak is not fragile in the traditional sense. Certainly not in the same way as, say, the fine china you only bring out on holidays. But it does suffer a hidden weakness; it is vulnerable to progressive internal fracturing from stress and damage over a certain level. It is not even particularly vulnerable to this compared other objects. The danger is more that we continue to treat such vast stores of potential energy as remaining invulnerable through these shocks. We continue to live and venture beneath them without much thought or concern, gazing up a few moments after a storm and nodding “ah, all still standing” and thinking perhaps the rake the only tool required in such moments.

But unlike bone, an oak does not grow back stronger than before – it suffers stoically and hides its inner fractures and rot shockingly well. The tree will stand looking mighty and invincible until suddenly it collapses totally. The willow–oft contrasted–is not the anti-oak. We focus too much on what’s above the ground. If we care about integrity, we should look far more to the pith and roots. If we care about resiliency and regrowth, we should start studying the reed and its humble rhizome.

In situations when any green object poking above the surface risks immediate attack, the rhizome thrives and propagates. The reed’s more infamous cousins – bamboo, ivy, kudzu–all use this strategy. So do most taboos currently outside the moment’s Overton window. Stability and tolerance, ironically, often slow the spread and hold these plant to their little walled patches of sunlight and comfort. But faced with elimination, constant stress, violence, damage that destroys its surface matter but swiftly moves on, the rhizome survives to spread and strengthen. When the mighty oak seeks to mimic this strategy as it ages –to suck every last drop from its domain and cement its dominion–and thus changes from its tap root to a root network, it mostly trades depth for breadth and retains or increases its central vulnerabilities. As it becomes ever more top-heavy, such trees become more perfect levers for even the minor gust–their relative grip on the earth become ever shallower and dependent on the status quo. A sudden rain after a drought and the largest trees collapse.

We call the more successful vines and shoots of the rhizomes invasive. That’s another word for winning. If we don’t like what’s winning, we might take a closer look at the environment and soil we’ve cultivated. The root wins in a well-drained nutrient-rich earth where slow strong foundations lead to towering edifices that seize the light and smother thieving opportunists. But upon collapse, a single tree’s fall creates a void beneath it and all that has been suppressed surges. Only then do we noticed the dearth of saplings beneath the old titan. When the surface world remains fresh razed and raw, little outcompetes the organism that grows its bulk underground before even seeking its first light. Within weeks, a tangle of alien foilage – shocking verdant and rendering the landscape unrecognizable.

That’s what we’re facing and fighting this year. The shoots and shootings you see are just now peeking out from vast networks long propagating in soil far too shallow, windblown, and impatient for new oaken artifacts. Stop focusing on the trees. Start looking at what’s beneath your own feet. And what isn’t.

—

With that in mind, who knew Aerosmith lyrics could age so well?

There’s something wrong with the world today

I don’t know what it is

Something’s wrong with our eyes

We’re seeing things in a different way

And God knows it ain’t his

It sure ain’t no surprise

Speaking of aging better than whiskey (in a jar or otherwise):

No Leaf Clover (Metallica live with the SFSO)

Pay no mind to the distant thunder

New day fills his head with wonder, boy

Says it feels right this time

Turned it ’round and found the right line

Good day to be alive, Sir

Good day to be alive, he said, yeah

Then it comes to be that the soothing light

At the end of your tunnel

Is just a freight train coming your way

The Deftones have clearly been paying attention this year:

Ooh, we sip from the fountain of intent

And ooh, we choke on the water, then repent